You may read this article on Medium if you wish.

You have decided to write a mystery novel. You sit at your desk, pencil in hand, excitement about to pour onto the page. You focus the excitement into the first sentence. You tell us about a detective who has just begun the toughest case of his life. He collects the evidence, he interviews the witnesses, he follows the clues. You are near the end of the story. It is nearly time to reveal the culprit. Your pencil nearly meets the paper…and then halts.

What if this person really isn’t guilty? What if this isn’t the entire story? What if the detective was merely an unwitting pawn in a much larger, and more dangerous, game?

Your writing completely changes directions. Now, the conflict is not only between multiple characters, but between you and the creative process. The original idea for your story was fine. Readers would have loved it. You were ecstatic as you approached the ending. Yet now, your mind seems fixated, even obsessed, with this new idea. The story appears to have taken on a life of its own. Why does this happen?

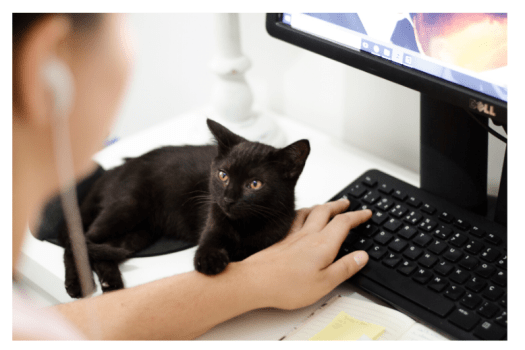

Consider a housecat (I have used this analogy before): it does not appear when called. Even if one baits it with treats, there are no guarantees. The cat may appear to obey commands, but it is not truly loyal to you; it is loyal only to its treats and whims. If it ceases to obey commands or be persuaded by the treats you have offered, then something else has captured its interest. Therefore, the only way to keep its attention is to follow its interests, rather than your own.

So it is with the creative process. Attempts to control it in the same manner in which one controls a mechanical tool often meet with failure. The creative process is not a mere tool; it bears greater resemblance to a person. It cannot, and should not, be controlled. It need only be guided, and, where necessary, followed.

This requires a high degree of trust between a creator and the process. We are accustomed to control. We are used to predictability. This is not wrong, of course. Without these things, life could easily turn into chaos. For many professions, procedure is critical. One must be able to predict that an aircraft will function safely, or that a medicine will cure a disease, or that a building will not collapse.

Creativity, however, seems to function differently. As stated in a previous article, any attempt to impose set procedures onto it appears to destroy it. It cannot be led. It does the leading. Many creators spend their entire lives learning how to trust its lead, even when its destination is not clear.

How does one accomplish this when a deadline nears? In the professional world, “writer’s block” is no more valid an excuse than “doctor’s block” would be to a surgeon. A film soundtrack must be completed before the film is released. A book must be published by a certain date to maximize sales. A musical composition for the concert hall must be completed in time to allow the performers to rehearse it. How does one make the creative process reliable while still ensuring a good, original result?

The aforementioned trust is one side of the coin. The other side is the editor. We all know him. In a previous article, I called him the “traffic cop.” He is the one who guides the process once it has done much of its work. He is the one who ensures that a composition does not veer “off the rails.” He makes certain that the work is understandable to an audience. He guarantees that a work remains within the scope of what is called for. After all, one would not compose a symphony when only a thirty-second commercial jingle was required. One would not paint an ultra-realistic landscape if only a picture of a flower was needed. One would not write a novel if only a blog post was requested.

One may take small ideas and develop them further, of course. Some of my best ideas (though perhaps I should allow the listener to be the judge) have begun as simple tunes. Melodies originally intended only to introduce television shows have been arranged into full concert suites (the Star Trek music is notable for this). Conversely, melodies from large-scale symphonies or suites have become so popular that they are often repurposed for commercial applications (with examples too numerous to list here). The creative process is remarkably adaptable. In fact, this adaptability requires and reinforces a different sort of trust. The “cat” and the “traffic cop” must learn to trust each other, and the creator must learn to trust both.

For Discussion

- How have you learned to trust your “inner traffic cop” and your “inner cat”?

- Does your creative process resemble this, or is your experience different?

- Have you ever created an idea with one purpose, only for it to change later?